Policy Recommendations

•Experiment with impact-based agreements to align policy, funding, and actions to drive progress toward an AIDS transition, with attention to rights and gender issues.

•Measure what matters — new infections and AIDS-related mortality — to achieve maximum value for spending through better targeting and alignment of financial support with countries’ own financial commitments and progress on prevention and treatment.

•Create incentives for co-financing by committing to a floor of support in hard-hit countries and developing matching funds for each additional person tested or on treatment.

Remarkable progress has been made in the global fight against HIV/AIDS. The number of people receiving treatment in low- and middle-income countries increased from 300,000 in 2003 to 13.7 million in 2015, including 7 million supported by the United States. AIDS-related deaths have dropped by 29 percent since 2005.

These gains are primarily attributable to a 2003 US government initiative called PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) that provided major new multiyear funding for global HIV/AIDS and created a new entity, the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, headed by an ambassador-rank Global AIDS Coordinator who is authorized to allocate PEPFAR’s resources and coordinate all US bilateral and multilateral activities on HIV/AIDS.

The Global AIDS Coordinator has wide authority over HIV/AIDS activities implemented by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the US Department of Health and Human Services (primarily through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health [NIH]), the Departments of Labor, Commerce, and Defense, and the Peace Corps. US leadership is recognized worldwide as having spurred an unprecedented surge in political commitment, global spending, and scientific advancement, which has transformed AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable disease.

However, without dramatic changes to PEPFAR, the next president risks being held responsible for the failure of a program that until now has been one of the United States’ proudest foreign assistance achievements. And because PEPFAR is a major component of US foreign assistance spending, the next president’s choices about PEPFAR will heavily influence any subsequent assessments of his or her humanitarian foreign assistance policies.

While the United States had played a role in the global response to AIDS since the mid-1980s, the creation and authorization of PEPFAR in 2003 marked a turning point in terms of funding and attention given to the epidemic. Through the US Leadership against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003, $15 billion over five years was allocated to PEPFAR to address HIV/AIDS in the hardest-hit countries and make contributions to multilateral agencies such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund). In 2008, PEPFAR was reauthorized for an additional five years at up to $48 billion, and in 2013 Congress extended PEPFAR’s authorities through 2018.

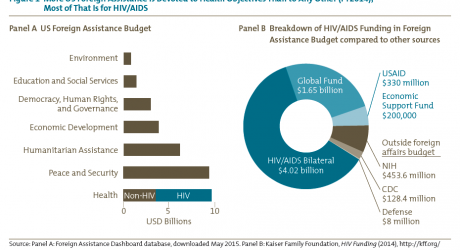

More US foreign assistance spending, $8.4 billion in 2014, is devoted to health objectives than to any other broad category (the bottom bar in the left panel of figure 1). PEPFAR funding to combat the HIV/AIDS epidemic includes not only $6 billion from the foreign assistance budget, but also an additional $580 million channeled through the NIH and the CDC (right panel of figure 1). PEPFAR is one of a very few bipartisan development priorities, with executive and congressional leaders in both political parties generally agreeing on the program’s objectives and strategy. Perhaps as a result of this rare political collaboration, the program is the largest foreign assistance program in history to address a single health issue and has spent a total of $51 billion from its launch in 2004 through the end of 2014, with $6.6 billion authorized for 2015 and $6.3 billion requested for 2016.

PEPFAR’s importance to US foreign assistance policy derives not only from its size but also from several other unusual or unique characteristics. It is the only foreign assistance program that directly provides long-term medical treatment, thus arguably endowing those patients with a virtual entitlement to continued US support.[6] PEPFAR is also the vehicle through which the United States is experimenting with channeling foreign assistance through the Global Fund, a multilateral institution quite different from the traditional Bretton Woods ones like the World Bank.[7] Along with the Millennium Challenge Corporation, another innovative foreign assistance program, PEPFAR sits outside of USAID and thus has the freedom to adopt new approaches to improving the effectiveness of foreign assistance. Like the Department of Homeland Security, PEPFAR attempts to rationalize and coordinate government bureaucracy, in its case by organizing HIV/AIDS-related programming across multiple government agencies, including not only the State Department, USAID, and the CDC but also Health and Human Services, the Department of Defense, and the NIH. Furthermore, the United States provides nearly two-thirds of all international assistance for HIV/AIDS, which together with its 33 percent contribution to the Global Fund makes its support critical to the sustainability of the global effort against AIDS. All of these features together suggest that whether PEPFAR continues to succeed or is humbled by its growing challenges will have repercussions for good or ill not only on the United States’ international reputation but also on the effectiveness of its foreign assistance policy overall.

Because US financing, both bilateral and multilateral, has dominated the global battle against HIV/AIDS, choices by the next administration will largely determine the health and financial burdens of the disease in severely affected countries through 2020 and beyond. If PEPFAR continues on its current path, the burden of HIV/AIDS in hard-hit, low-income countries threatens to consume an ever-increasing share of national health spending, perpetuate most recipient countries’ dependency on foreign donors, and indefinitely postpone the achievement of an AIDS-free generation. Therefore, the next US president must reinforce and continue the US government’s commitment to reducing HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths by ensuring PEPFAR’s programs establish clearer incentives for progress and partner-country investment. This can be done by

•aligning funding to reward progress toward the AIDS transition;

•allocating more funding to measure new HIV infections; and,

•specifying future US commitments to focus countries as a foundation for strengthening co-financing schemes.

Read more here http://www.cgdev.org/publication/ft/strengthening-incentives-sustainable-response-aids-pepfar-aids-transition?utm_source=150818&utm_medium=cgd_email&utm_campaign=cgd_weekly&utm_&&&